I just spent a week in Hawaii – the first real vacation I’ve had in years, but my brain didn’t stop racing the whole time. I am the worst vacationer and here are the three things I think I’ve been thinking about.

1) I Fixed the BLS’s Payrolls Problem (sort of, ha).

The big news in recent weeks was the fiasco around last month’s payrolls data. The revisions were gigantic and sparked a good deal of controversy. This isn’t really a new thing and it isn’t really an important thing either since the data always gets reconciled with the QCEW data which can’t be manipulated. So, unless you’re frantically trading around the monthly payrolls report then this is largely irrelevant to you because it all comes out in the wash in the long-run. But it still raises an important question about the validity of monthly survey data that tends to be pretty error-prone on its initial read.

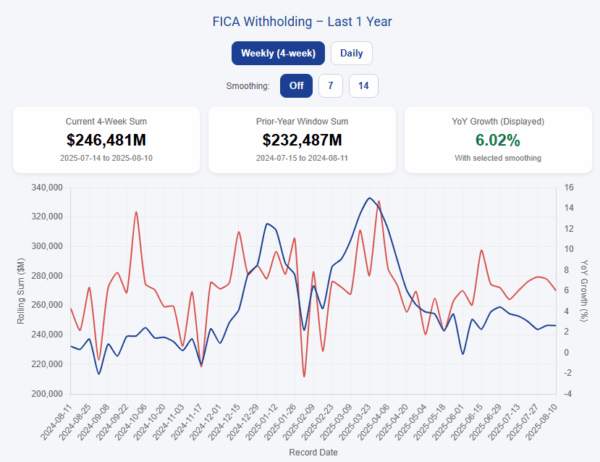

One common response to this problem was “well, we have real-time FICA tax data so why don’t we just pull that?” And so I spent a good deal of my vacation nerding it up building a tool that does exactly that. In the Macro Dashboard you’ll find a fully updated tool for FICA Withholding. It pulls custom data across time horizons of your preference to give us some idea of what aggregate payroll incomes look like. It’s nice in that it is pulling actual income tax data so it can’t be fudged and it’s not based on surveys and subjective inputs.

Of course, this isn’t pulling 1099s and there’s an annual National Average Wage Index (NAWI) adjustment so we’re not getting a perfectly clean read on the labor market, but it’s a nice complement to survey data that can be error prone and subject to huge revisions. I’d add it’s especially useful in tandem with jobless claims, which are also a better real-time metric for the labor market.

A common criticism of FICA data is that it’s adjusted for average wages each year so the data could grow for no other reason than the wage adjustment. So I added a NAWI Incidence adjustment scale to give the option to adjust for this as desired. But it’s impossible to know what percent of FICA reports actually apply there so I left it somewhat conservative. It you scale it to 1 it would offset the entire NAWI adjustment which is pretty unrealistic since it doesn’t bleed through the data 1:1.

As of yesterday the data was showing 6.02% year over year growth (5.26% with the NAWI adjustment) which would equate to roughly 2.26% real growth in payrolls. Not bad. Again, nothing to be too alarmed about and largely in-line with what we’re seeing in broader data like GDP. But it’s also not booming in real terms and more in-line with what I’ve been referring to as a Covid mean reverting “muddle thru” period.

Anyhow, give the tool a test drive and feel free to check out some of the other tools I’ve been building in the meantime. If you have any feedback feel free to ping me. And if you have other ideas for tools like this just let me know. I think we’ve covered most of the big indicators now with the Leading Inflation Index, the Recession Rule and the Employment Data, but the more the merrier.

2) Should You Jump on the Private Equity Bandwagon?

Here’s a wonderful article from Jeff Ptak at Morningstar on private equity funds and alternatives more broadly. Jeff highlights a pretty shocking stat: 75%+ of alternative funds have been shutdown since 2006. He highlights a bunch of good lessons to keep in mind on this.

I go back and forth about the use of alternatives. It’s just such a big space that I don’t think you can make sweeping generalizations. I tend to try to keep things simple with just stocks and bonds for asset allocation purposes, but there are strong arguments for other diversifiers depending on someone’s specific situation. I like to position “alternatives” as a form of insurance. For example, a highly active option writing fund is essentially taking a stock allocation and then embedding an insurance overlay to throttle the volatility of the underlying stocks and/or generate some offsetting income for stability. Is that necessarily bad? It depends on lots of different factors like the cost of that insurance and how it would fit into your overall portfolio. But I don’t think we should say it’s inherently bad.

As a general rule I think investors should confront alternatives and portfolio insurance the same way we confront something like life insurance – with skepticism, but not irrational dismissiveness. Life insurance is a great product. For the right person, at the right time in life. But it’s not something that should be broadly shoved down everyone’s throat or dismissed entirely. It is very much case contingent. I’d also add the type of insurance you’re considering makes a big difference here. If you’re considering some fancy sounding long/short equity fund there isn’t a lot of evidence that that’s a great option when compared to a much simpler portfolio like a 60/40. So the long/short fund ends up being more akin to whole life insurance vs term. Term life is the inexpensive option that gets the job done sufficiently while whole life insurance is the expensive option that probably gives you more protection than you really need (and ends up costing a lot in the process). But again, you can’t paint with too broad of a brush about this stuff because money and portfolio preference needs to be personalized at a financial planning level.

As it pertains to portfolio insurance more specifically I think the case for alternatives becomes a lot less compelling when T-Bills are yielding a positive real return. Cash is, after all, arguably the best form of portfolio insurance and when it’s earning a real return it operates as both a nominal and real hedge in your portfolio. That’s pretty hard to beat if you’re looking for something to insure the rest of your portfolio.

Anyhow, it’s all timely given the surging popularity of private equity ETFs and various funds trying to diversify outside of bonds and cash. Give Jeff’s piece a read. It’s very good.

3) Is “Stocks for the Long Run” All Wrong?

Here is one of the best panel discussions I’ve watched in a long time. The panel was comprised of Edward McQuarrie, Rob Arnott, Elroy Dimson, Roger Ibbotson, and Jeremy Siegel. Larry Siegel moderated. What a lineup.

The discussion revolved largely around a new paper by McQuarrie which questioned the standard view on “Stocks for the Long Run” and the idea that you can’t lose if you hold equities for a long enough period. As you can probably guess, I love any discussion about time horizons and investing. And I especially love any discussion that adds some nuance to subjects like “stocks for the long run”. After all, what the heck does that mean? Is the long-run a month? A year? A decade? We don’t generally quantify this idea which naturally leads to confusion and misguided expectations. I like the McQuarrie paper because it tempers some of the expectations around stock returns. There’s a tendency to view stocks as a slam dunk instrument over the long-term and that sometimes leads people to consider allocating their entire portfolio to stocks. But it’s a lot more complex than that.

First, we don’t live within one time horizon. When I developed the Defined Duration strategy the main goal was to emphasize that we live our lives across lots of time horizons. A good portfolio isn’t just about optimizing risk relative to returns. It should be about optimizing risk relative to returns based on the time horizons over which you’re likely to eat those returns. And if you need money in five years, for instance, you cannot reliably create a stock portfolio to be able to consume. We consume over lots of time horizons and a good portfolio should optimize that for certainty over appropriately corresponding time horizons.

Second, even if the stock market is a high probability bet in the long-run it can be a high improbable bet as you wait. I abandoned the traditional risk profiling process in recent years in large part because I realized that selling into bear markets isn’t really a fear factor. People sell low in bear markets because they hate the uncertainty it creates. You’re not just scared of the asset you own. You are scared by the fact that it makes your financial life uncertain in the short-term. This isn’t an emotional issue. It’s a portfolio imbalance issue. For instance, if you consume $50,000 a year and you have $500,000 of T-Bills and $500,000 of stocks and the stock market falls 50% then you really don’t care about the stock performance because you don’t have an imbalance in your portfolio. Your assets and liabilities align (well kinda – you probably own way too many T-bills, but you get the point hopefully). Sure, the stock market decline is still scary, but you’re more robust to the decline because you can see, in a very tangible way, that you have many years worth of liquidity to ride out the volatility in that $500,000 stock allocation. You don’t get scared because you have short-term assets that align with your short-term spending needs. This isn’t a behavioral issue. It’s an asset-liability matching issue!

Anyhow, I am sorry. I got a little excited about asset-liability matching there and I started to ramble. But if you have an hour give the panel a listen. These are giants of our industry and always worth listening to.

4) Bonus 4th Thing, which is Really the same as the Second Thing.

When I was writing my forthcoming book I focused an entire chapter on dividend investing and income generation. I wrote specifically about the income and anti-income perspective. From an academic/theoretical perspective I’ve never been a big fan of dividends. They are just taxable payments that distribute from net assets. That’s why buybacks have become so popular in recent years – they give the income/tax optionality to the shareholder instead of having the corporation impose the tax liability on everyone who owns the stock. But from a behavioral finance perspective I think dividends are great because income gives people clarity. While capital gains are uncertain a stream of income can be much more certain.

But there’s a really dark side in the income generation discussions. A reasonable and sustainable level of income (for example, a 2.5% dividend yield from something like the Vanguard High Dividend ETF) is wonderful. The income generating entities are generally a bit safer and they provide the investor with a reliable stream of consistent income with the potential for added principal appreciation along the way. That’s great. But in recent years a whole bunch of trash products have developed that sell the allure of high income and do it in very nasty ways.

I won’t belabor the point because Benn Eifert wrote an incredible Twitter thread on the rise of some of these products. Go give it a read. Benn is one of the gatekeepers of modern finance who does a great job highlighting mines in the minefield of financial products.